The brain-eating amoeba, scientifically known as Naegleria fowleri, is as rare as it is deadly. Despite fewer than 10 people in the United States contracting this infection annually, the death rate exceeds a staggering 97%. Between 1962 and 2024, only 167 cases have been reported nationwide, with merely four individuals surviving this devastating infection.

What is brain-eating amoeba exactly? Naegleria fowleri is a free-living ameba that thrives in warm freshwater environments such as lakes, rivers, and hot springs. Infection typically occurs when contaminated water enters the nose during swimming activities, particularly in summer months when water levels are low and temperatures are high. Unfortunately, once symptoms of brain-eating amoeba begin to appear, patients usually succumb to the disease within two weeks. Although brain-eating amoeba survivors exist, they are exceptionally rare, making early recognition and medical intervention critically important. This article delves into the facts about this microscopic threat and provides essential information on recognition, prevention, and treatment options.

What is a brain-eating amoeba?

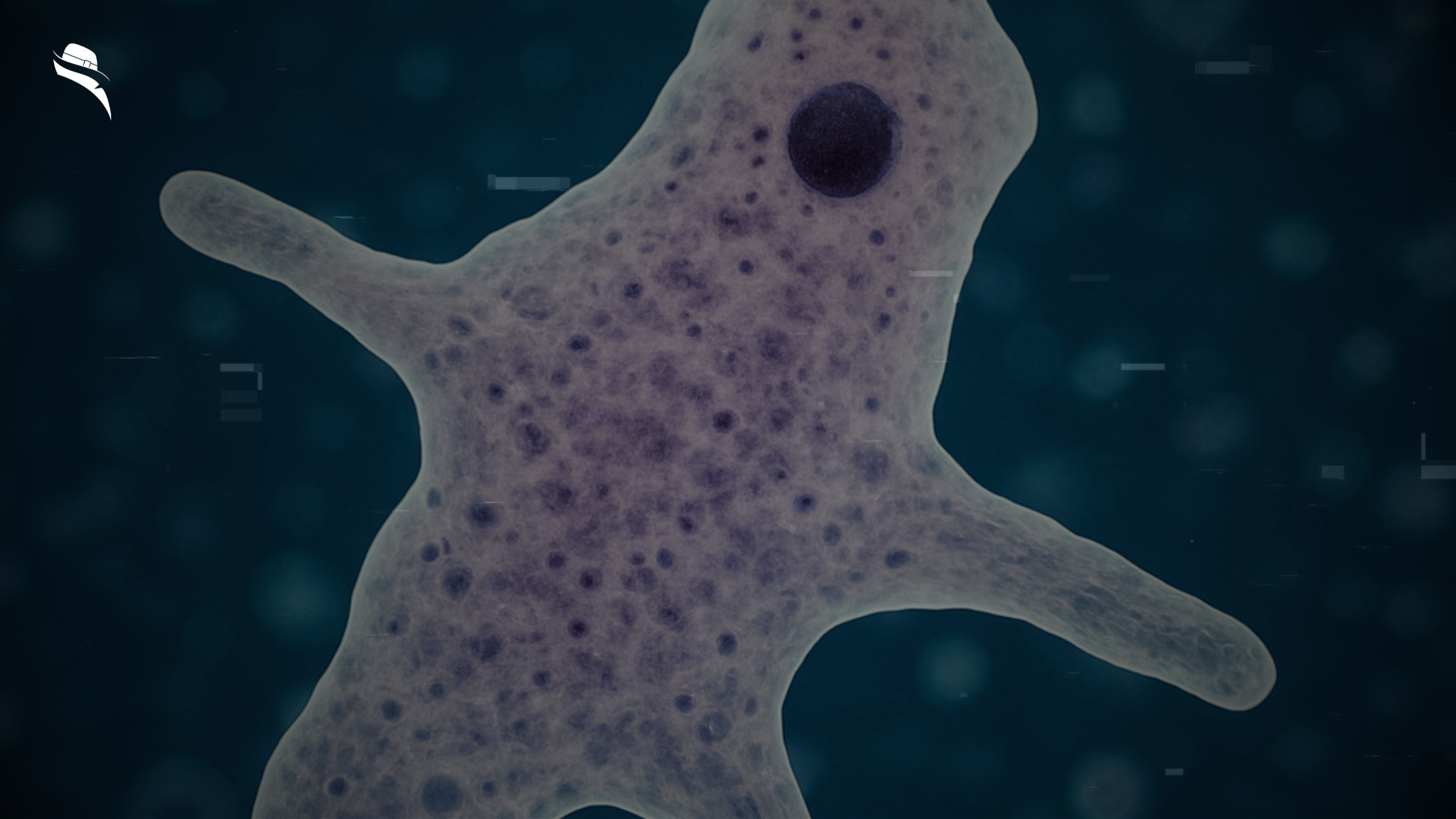

Discovered in 1965, the brain-eating amoeba (Naegleria fowleri) is a single-celled organism that belongs to the amoeboflagellate excavate group, capable of existing in three distinct forms: cyst, trophozoite, and flagellate. This microscopic organism normally feeds on bacteria in its natural environment, but can become deadly if it enters the human body.

Where Naegleria fowleri is found

This free-living microorganism thrives in numerous environments across the globe. N. fowleri primarily inhabits warm freshwater bodies, including lakes, rivers, ponds, and hot springs. Additionally, it can be found in soil, sediment, dust, sewage, and untreated water sources. In rare instances, the amoeba has been detected in poorly maintained swimming pools, splash pads, water parks, and even tap water systems. Unlike many pathogens, this amoeba can survive in domestic water heaters and has been isolated from the nasal passages of healthy individuals who never developed an infection.

How does it survive in warm environments?

N. fowleri is classified as thermophilic, preferring water temperatures between 35°C and 46°C (115°F). This heat-loving characteristic explains why infections typically increase during summer months. Furthermore, the amoeba can tolerate pH levels ranging from 4.6 to 9.5, making it adaptable to various water conditions. To endure harsh environmental conditions, trophozoites transform into protective cysts that enable survival during food scarcity, overcrowding, desiccation, or cold temperatures. Interestingly, these cysts can survive winter in lake sediments, re-emerging when conditions become favorable.

Why it called a brain-eating amoeba

The nickname “brain-eating amoeba” stems from how N. fowleri behaves after entering the human body. Once it reaches the brain, the amoeba consumes erythrocytes and nerve cells, causing devastating damage and inflammation. However, brains are not their intended food source—they’re an accidental target. According to health authorities, N. fowleri normally eats bacteria in its natural environment. The amoeba causes a rare but nearly always fatal brain infection called primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), which is why this microscopic organism has earned its frightening moniker.

How infection happens and who is at risk

Infection with brain-eating amoeba occurs through a specific pathway that makes this rare disease both difficult to prevent completely, yet remarkably uncommon considering widespread exposure.

How the amoeba enters the body

Naegleria fowleri infiltrates the human body exclusively through the nose, never through the mouth or skin. Once inside the nasal cavity, the amoeba travels upward along the olfactory nerve, crossing the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone to reach the brain. Studies suggest these microscopic organisms are actually attracted to chemicals used by nerve cells for communication. Upon reaching brain tissue, the amoeba begins destroying cells rapidly, causing massive inflammation and hemorrhage.

Common exposure scenarios

Most infections occur under specific circumstances:

- Swimming, diving, or water skiing in warm freshwater lakes, rivers, or ponds during summer months

- Water activities are recommended when temperatures have been high for extended periods, resulting in warmer water and lower water levels

- Using contaminated tap water for nasal irrigation or sinus rinsing

- Religious practices involving submerging the head in water

- Extremely rarely, exposure through inadequately chlorinated swimming pools, splash pads, or surf parks

Notably, you cannot contract this infection by drinking contaminated water, swimming in properly maintained pools, or from another infected person.

Why do some people get infected and others don’t

Despite Naegleria fowleri being relatively common in warm freshwater across the United States, infection is extraordinarily rare. Between 2010 and 2022, only 40 infections were reported nationwide. This striking discrepancy between exposure and infection suggests several possibilities.

Research indicates many people may have antibodies to the amoeba, suggesting their immune systems successfully fought off infection. Studies also show humans appear more resistant to infection than laboratory animals. The risk of primary amebic meningoencephalitis from swimming once in water containing 10 amoebae per liter is estimated at just 8.5 × 10−8, explaining why most exposures never result in disease.

Symptoms and disease progression

Primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) progresses with frightening speed once symptoms begin to appear.

Early symptoms of brain-eating amoeba

Initially, patients experience symptoms similar to many common illnesses – headache, fever, nausea, and vomiting. Some may also develop a sore throat and blocked nasal passages. These initial symptoms typically appear 1-7 days after exposure, though the range can extend from 1-12 days.

How symptoms mimic other illnesses

The early manifestations of PAM often resemble bacterial meningitis or other more common infections. This resemblance makes proper identification exceptionally challenging in the critical early stages. Symptoms like fever and headache are frequently attributed to more common conditions, consequently delaying life-saving treatment.

Timeline from exposure to death

As PAM advances, patients develop more severe symptoms, including:

- Stiff neck and photophobia

- Confusion and lack of attention to surroundings

- Seizures and hallucinations

- Coma

Within 3-4 days after initial symptoms, mental confusion and coma typically occur. The progression from first symptoms to death usually spans 5 days, though cases range from 1-18 days. Generally, death follows coma within 3-4 days.

Why is early diagnosis difficult?

Diagnosing brain-eating amoeba requires specialized testing, primarily available in limited laboratories. Moreover, since symptoms overlap with numerous other conditions, physicians rarely suspect PAM until traditional treatments fail. Unfortunately, nearly 75% of diagnoses occur post-mortem.

Treatment options and survival chances

Treatment options for brain-eating amoeba remain limited, yet medical advances offer glimmers of hope amid otherwise grim statistics.

Drugs used in treatment

Medical professionals employ a specific combination of medications to combat Naegleria fowleri infections. The cornerstone treatment involves amphotericin B administered both intravenously and intrathecally (directly into the spinal fluid). Other critical medications often include:

- Miltefosine (imported from Germany for some cases)

- Fluconazole

- Rifampin

- Azithromycin

- Dexamethasone to reduce brain swelling

Why is survival rare

Even with aggressive treatment, the mortality rate exceeds 97%. This devastating statistic stems from several factors. First, the disease progresses with exceptional speed, often causing death within 7-10 days after infection. Second, the amoeba causes massive intracranial pressure that proves fatal in most cases. Finally, effective drug concentrations must penetrate the blood-brain barrier, a significant challenge.

Stories of brain-eating amoeba survivors

Only eight people worldwide survived PAM between 1971 and 2023. Among them is Kali Hardig, who in 2013 was given a 1% survival chance. After doctors administered miltefosine and induced therapeutic hypothermia, Kali recovered, though she required extensive rehabilitation. Similarly, Sebastian DeLeon’s 2016 survival in Florida marked a historic case where cooling his body temperature helped halt the amoeba’s reproduction.

Importance of early medical attention

Timing proves absolutely critical. Survivors typically received a diagnosis and treatment within 24-72 hours of symptom onset. In Afnan’s case from India, diagnosis occurred within 24 hours, allowing for immediate administration of antimicrobial drugs. Conversely, delayed diagnosis virtually guarantees fatal outcomes.

Final Thoughts

While awareness of brain-eating amoeba remains limited, education has become a crucial mission for families who have lost loved ones to this deadly infection. “We can’t bring Aven back, but if we can save one other person, we’re doing our best,” shares Debra Moffat, whose family established a website to spread information about Naegleria fowleri after losing their son.

Even as climate change expands the geographical range of this pathogen into northern states like Nebraska, Minnesota, and Indiana, experts stress that PAM is “99% fatal but 100% preventable“. Nevertheless, the “rare” label often assigned to this infection may create a false sense of security.

Indeed, rising global temperatures not only expand the amoeba’s habitat but may increase human exposure as more people seek water for recreational activities. Yet experts emphasize that this threat shouldn’t prevent summer enjoyment.

For those experiencing headache, fever, nausea, or vomiting after swimming in freshwater, immediate medical attention is vital. At the same time, researchers continue working toward better treatments, as current options remain severely limited.

Looking ahead, successful management of this deadly pathogen will require improved diagnostics, innovative therapies, enhanced surveillance, and coordinated global efforts to address climate change impacts.

FAQs About the Brain-Eating Amoeba (Naegleria fowleri)

1. What is a brain-eating amoeba?

The brain-eating amoeba, scientifically known as Naegleria fowleri, is a microscopic, single-celled organism found in warm freshwater. It causes a rare but almost always fatal brain infection called primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM).

2. Where is Naegleria fowleri commonly found?

This amoeba thrives in warm freshwater environments such as lakes, rivers, hot springs, and even poorly chlorinated swimming pools. It has also been found in soil, dust, and domestic water systems.

3. How does someone get infected with a brain-eating amoeba?

Infection occurs when contaminated water enters the nose, typically during swimming or diving in warm freshwater. The amoeba travels through the nasal passage to the brain, where it causes severe inflammation and destruction of brain tissue.

4. Can you get infected by drinking contaminated water?

No. You cannot get infected by drinking water contaminated with Naegleria fowleri. The amoeba must enter through the nose to cause infection.

5. What are the symptoms of brain-eating amoeba infection?

Early symptoms include headache, fever, nausea, vomiting, and a blocked nose. As the disease progresses, patients may experience confusion, seizures, hallucinations, and coma.

6. How quickly do symptoms appear after exposure?

Symptoms usually begin 1 to 7 days after exposure, and the disease can progress rapidly, often resulting in death within 5 to 10 days.

7. Why is the brain-eating amoeba so deadly?

The amoeba destroys brain tissue rapidly and causes massive inflammation. Diagnosis is often delayed, and current treatments have limited success. The survival rate is less than 3%.

8. Is there any treatment for brain-eating amoeba?

Yes, but treatment is challenging. Doctors use antifungal and antimicrobial drugs like amphotericin B, miltefosine, rifampin, and azithromycin. Cooling the body (therapeutic hypothermia) has helped in rare survival cases.

9. Has anyone survived a brain-eating amoeba infection?

Yes, but survival is extremely rare. Only a handful of people worldwide have survived, often thanks to early diagnosis and aggressive treatment within 24 to 72 hours of symptom onset.

10. Who is most at risk of infection?

People who swim or dive in warm freshwater during summer are at higher risk. Children and young adults are most commonly affected due to their water activity levels.

11. Can the brain-eating amoeba be spread from person to person?

No. The infection is not contagious and cannot spread from person to person.

12. What steps can I take to prevent infection?

Avoid swimming in warm freshwater when temperatures are high and water levels are low. Use nose clips or keep your head above water. Never use untreated tap water for nasal irrigation without boiling or filtering it first.

13. Can brain-eating amoeba survive in swimming pools?

Only in pools that are poorly chlorinated. Properly maintained pools are generally safe.

14. Why are infections so rare despite wide exposure?

Many people may develop immunity, or the infection may require specific conditions to occur. The estimated risk from a single swim in contaminated water is extremely low.

15. Is climate change affecting the spread of brain-eating amoeba?

Yes. Rising global temperatures are expanding the amoeba’s habitat into previously unaffected northern regions, increasing the risk of exposure during summer.

16. Should I avoid swimming in lakes and rivers altogether?

Not necessarily. Experts recommend caution rather than avoidance. Stay informed, follow prevention tips, and seek medical attention immediately if symptoms arise after water exposure.

17. How is PAM diagnosed?

PAM is diagnosed through specialized tests on cerebrospinal fluid, often performed too late due to symptom overlap with other illnesses. Faster diagnostics are being researched.

18. What’s being done to improve survival rates?

Scientists are working on better diagnostic tools, more effective medications, and public awareness campaigns. Early detection remains key to survival.

Leave a Reply