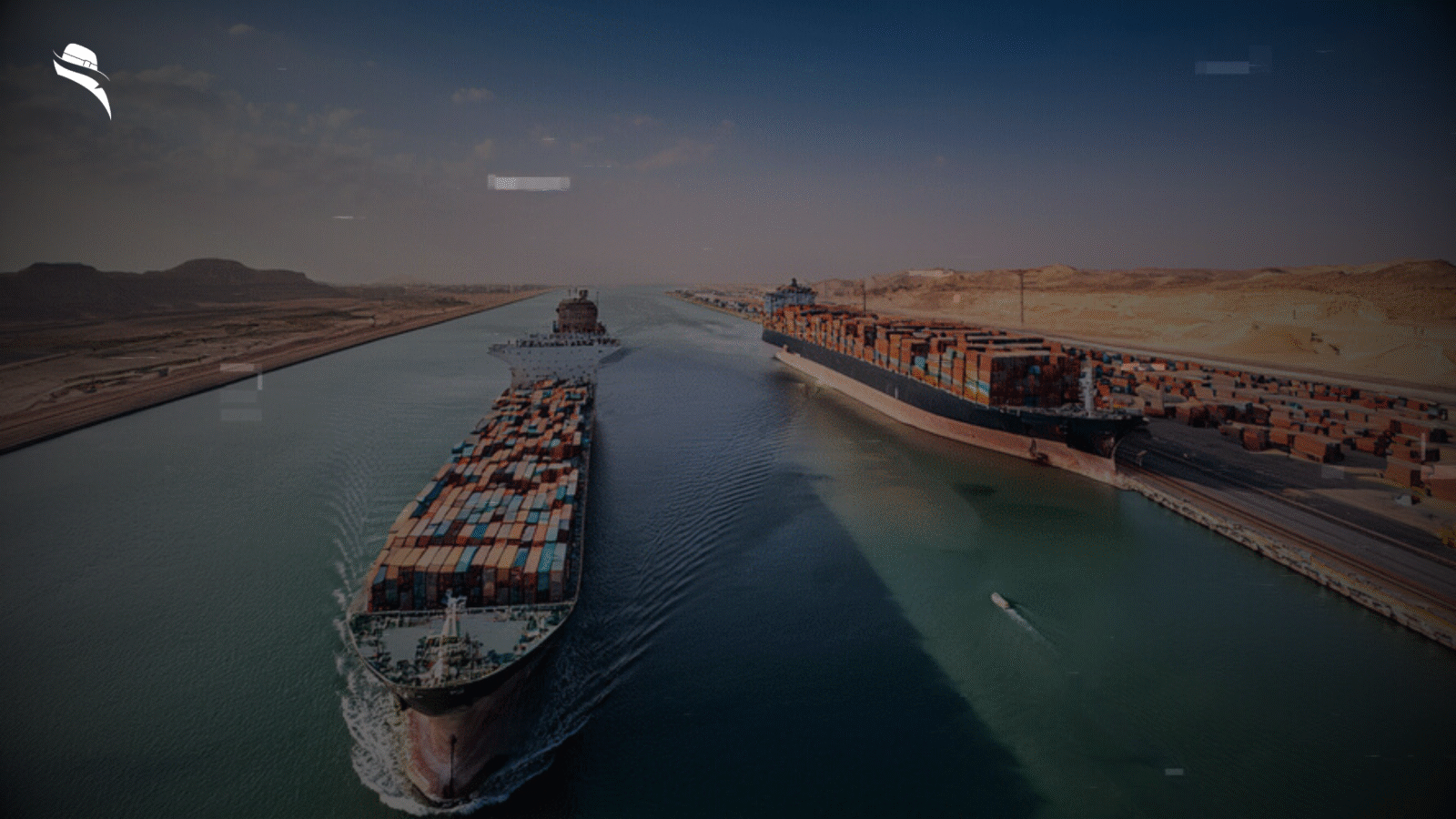

The importance of the Suez Canal stretches far beyond its impressive 193.3 km length, as approximately 12% of global trade, nearly $1 trillion in goods, passes through this critical maritime chokepoint annually. Connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea, this engineering marvel handles 7-10% of the world’s oil and 8% of liquefied natural gas, making it the second most important seaborne energy route after the Strait of Hormuz.

Why is the Suez Canal so important to world trade? Primarily, it significantly reduces maritime journeys by approximately 3,000 nautical miles compared to the route around Africa, saving ships 8-10 days of travel time. Furthermore, the Suez Canal significance becomes starkly evident when disruptions occur, as demonstrated during the 2021 Ever Given incident, which created a maritime traffic jam of over 200 ships and caused daily losses exceeding $9 billion.

Completed in 1869, the canal has maintained its geopolitical relevance for over 150 years, generating approximately $7 billion annually for Egypt’s economy. With traffic increasing to 18,880 vessels in 2019 and expansion through the New Suez Canal project in 2015, this vital waterway continues to shape international commerce, energy security, and regional politics in profound ways.

What Makes the Suez Canal a Global Trade Lifeline

“The geographical position of this waterway enables it to acts as a shortcut between the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea saving costs and shipping time.” — Dr. Rudolph Bayer, Professor of International Maritime Law

The Suez Canal stands as a testament to human engineering and serves as a vital artery for international commerce. This critical waterway connects two major bodies of water—the Mediterranean and Red Seas—creating an essential link between Europe and Asia that has shaped global trade patterns for over 150 years.

Geographic location and chokepoint status

The strategic value of the Suez Canal stems from its unique geographic position across the Isthmus of Suez in Egypt. At 193.3 kilometres long, this artificial sea-level waterway divides Africa from Asia while connecting two major seas. Its status as a maritime chokepoint cannot be overstated—approximately 12% of global trade flows through this narrow passage, representing 30% of worldwide container traffic and over $1 trillion worth of goods annually.

The canal processes nearly 19,000 ships per year—about 50 vessels daily—carrying between $3-9 billion worth of cargo. This immense volume highlights why the Suez Canal holds such prominence in global supply chains. Notably, the waterway carried over 1 billion tonnes of cargo in 2019, four times the tonnage that transited the Panama Canal during the same period.

Beyond commercial goods, the canal serves as a crucial energy corridor. It enables the transfer of an estimated 7-10% of the world’s oil and 8% of liquefied natural gas. Approximately one million barrels of oil traverse the Suez daily, underscoring its vital role in global energy security.

Reduction in travel time and shipping costs

The primary advantage of the Suez Canal lies in the dramatic reduction of maritime journey distances. Since its opening in 1869, the canal has shortened the route from Asia to Europe by approximately 6,000 kilometres by eliminating the need to circumnavigate Africa. This reduction translates to significant time savings—between 7 to 10 days, depending on vessel speed.

Consider these specific route improvements:

- Rotterdam to Mumbai: Distance reduced by 41%

- London to Shanghai: Distance shortened by 32%

- Persian Gulf to Northern Europe: A 21,000 km journey taking 24 days, reduced to 12,000 km taking just 14 days

These dramatic reductions yield substantial economic benefits. Shorter voyages mean less fuel consumption—a major expense in shipping operations. Additionally, reduced travel time translates to lower labor costs, decreased wear on vessels, and improved operational efficiency. The canal also enables shipping companies to complete more deliveries in less time, enhancing overall productivity and supply chain responsiveness.

Comparison with the Cape of Good Hope route

Without the Suez Canal, vessels would need to navigate around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope—the only viable alternative route between Europe and Asia. This detour adds approximately 8,000-10,000 kilometres to voyages, resulting in journey extensions of 10-15 days.

The disadvantages of the Cape route extend beyond mere time considerations. Ships choosing this path face:

- Increased fuel consumption and associated costs

- Higher crew wages due to extended voyage times

- Additional wear and maintenance requirements for vessels

- Elevated insurance premiums, particularly with rising piracy risks

- Substantially increased carbon emissions—a single container ship diverted around Africa releases an extra 5,400 tonnes of CO2, equivalent to the yearly output of 1,174 cars

Despite these drawbacks, some shipping companies occasionally opt for the Cape route when Suez Canal transit fees (which can reach $700,000 for a fully laden 20,000 TEU container ship) exceed potential savings. However, in normal circumstances, the Suez Canal’s efficiency and speed make it the overwhelmingly preferred option for global shipping.

Recent disruptions, including the 2021 Ever Given blockage and Houthi attacks in the Red Sea, have forced many vessels to divert around Africa, highlighting just how essential this maritime shortcut remains to global commerce and supply chain stability.

The Suez Canal in Historical Geopolitics

From its inception, the Suez Canal has been at the center of international power struggles, reflecting its strategic value beyond just commercial interests. Throughout history, this vital waterway has shaped global politics and triggered conflicts that reverberate to the present day.

Colonial ambitions and control battles

Initially constructed between 1859 and 1869 under the supervision of French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps, the Suez Canal quickly became a focal point for colonial competition. The canal’s opening created the shortest maritime route between Europe and Asia, instantly transforming it into a geopolitical prize.

In 1875, facing a financial crisis, Egypt was forced to sell its shares in the Suez Canal Company to the British government, which secured a 44% stake for £4 million. This transaction marked the beginning of British dominance over this crucial waterway. Subsequently, Britain’s 1882 invasion and occupation of Egypt solidified its control over both the country and the canal.

The 1888 Convention of Constantinople further institutionalised European influence, declaring the canal a neutral zone under British protection. This arrangement allowed international shipping to pass freely through the canal in both war and peace, though in practice, Britain maintained effective control. Indeed, by the early 20th century, the canal had become a cornerstone of British imperial strategy, particularly for maintaining connections with its colonies in Asia.

The Suez Crisis and Cold War alignments

The pivotal moment in the canal’s geopolitical history came on July 26, 1956, when Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal Company. This bold move was a direct response to the American and British decision to withdraw financing for Egypt’s Aswan High Dam project after Egypt established ties with communist Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union.

Accordingly, Britain and France, fearing loss of control over this strategic asset and the petroleum flowing to Western Europe, secretly prepared military action. They found a willing partner in Israel, which faced Egyptian blockades and border raids. On October 29, 1956, Israeli forces invaded Egypt, followed by British and French paratroopers landing near Port Said on November 5-6.

The intervention, however, prompted unprecedented Cold War tensions. Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev threatened to “rain down nuclear missiles on Western Europe”, while the United States, under President Eisenhower, pressured its allies to withdraw. By December 22, UN forces evacuated British and French troops, with Israeli forces withdrawing in March 1957.

This crisis fundamentally altered global politics. Nasser emerged as a hero of Arab nationalism. The Soviet Union gained influence in the Middle East. Meanwhile, Britain and France saw their status as world powers diminish dramatically. For the United States, the crisis prompted deeper involvement in Middle Eastern affairs, eventually leading to the Eisenhower Doctrine of 1957, which pledged American economic and military aid to contain communism in the region.

Economic Powerhouse: Trade, Oil, and Revenue

“Approximately 12% of international trade, 10% of international oil and gas shipments, and 22% of container trade passes through the Suez Canal.” — Al-Majalla Economic Research Team, Middle East Economic Analysis Group

As a critical conduit for world commerce, the Suez Canal generates enormous economic value while serving as the backbone of Egypt’s economy. This artificial waterway processes much more than ships—it facilitates the flow of global wealth and energy resources that sustain international markets.

Importance of the Suez Canal in global trade volume

The Suez Canal handles approximately 12% of global trade and 30% of worldwide container traffic, with goods valued at over $1 trillion transiting annually. On a typical day, about 50 vessels navigate the canal, carrying between $3-9 billion worth of cargo. In 2019, the canal accommodated 18,880 vessels, processing over 1 billion tonnes of cargo—four times the tonnage that passed through the Panama Canal during the same period.

Moreover, the canal’s strategic location significantly reduces shipping distances. A vessel travelling from Tokyo to Rotterdam saves approximately 3,315 nautical miles (23% distance reduction) by using the Suez route rather than circumnavigating Africa. Without this shortcut, ships rerouted around the Cape of Good Hope face journey extensions of at least one additional week.

Revenue generation for Egypt

Financially, the Suez Canal represents a vital income source for Egypt. Prior to recent disruptions, the canal generated record revenues of $9.4 billion in the 2022-2023 fiscal year. In fact, the canal typically contributes billions to Egypt’s economy annually, with tolls paid in foreign currency, particularly valuable given Egypt’s struggle with inflation.

Unfortunately, regional conflicts have severely impacted these revenues. The Houthi attacks in the Red Sea since November 2023 have reduced canal traffic by approximately 50% year-over-year. President Sisi reported monthly revenue losses of around $800 million, with annual losses reaching approximately $7 billion in 2024.

Energy transit: oil and LNG flows

The canal’s role in global energy markets remains fundamental:

- 7-10% of the world’s oil and 8% of liquefied natural gas transits through the Suez Canal

- Approximately one million barrels of oil pass through daily

- In 2020, 686 LNG carriers (including 388 laden vessels) transited the canal, representing 7% of global LNG shipments

- These laden LNG carriers transported over 32 million tonnes per annum (mtpa)

Specifically, the canal facilitates crude oil flows primarily northbound from Persian Gulf countries (85% of northbound traffic) to Europe and North America. Conversely, southbound petroleum traffic has increased significantly, primarily from Russia to Asian markets like Singapore, China, and India.

Disruptions That Shook the World

Recent events have demonstrated the fragility of global supply chains when the Suez Canal faces disruptions. Two major incidents have exposed just how essential this waterway remains to international commerce and stability.

Ever Given incident and supply chain delays

March 2021 brought unprecedented disruption when the massive container ship Ever Given became wedged sideways across the canal. This 400-meter-long vessel, weighing 200,000 tonnes and carrying 18,300 containers, completely blocked the waterway for six days. The obstruction created a maritime traffic jam of 422 ships waiting on both sides of the canal.

The financial toll was staggering. Estimates suggested losses between $400 million per hour to $10 billion daily. By the time the ship was freed on March 29, analysts calculated that trade worth up to $10 billion had been halted daily. Even after the canal reopened, clearing the backlog took nearly a week as the canal authority pushed capacity to over 100 transits daily, double the normal volume.

Houthi attacks and insurance cost spikes

In contrast to the accidental Ever Given incident, a deliberate crisis emerged in late 2023. Since November, Houthi militants have conducted approximately 250 attacks on ships in the Red Sea, forcing many vessels to divert around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope—a journey that adds 4,000 miles and 10-14 days to transit times.

Consequently, insurance costs skyrocketed. Cargo insurance rates for Red Sea voyages jumped from the typical 0.6% of cargo value to 2%, plus additional war risk premiums. This triggered massive price increases in shipping: Drewry’s World Container Index showed rates leaping from $1,521 per 40-foot container to $3,777 between December 2023 and January 2024.

Impact on Egypt’s economy and global inflation

Beyond shipping disruptions, these crises have severely wounded Egypt’s economy. The Suez Canal Authority reported revenue plummeting by 40% in early 2024, with annual losses reaching approximately $7 billion. For Egypt, where canal revenues typically contribute about 2% of GDP and provide crucial foreign currency, this represents a devastating blow amid existing economic struggles.

Primarily, these disruptions threaten global price stability. If current shipping cost increases persist through 2025, global consumer prices could rise by 0.6%, with small island developing states facing up to 0.9% inflation increases. The interruption of disinflationary trends might rekindle broader inflation concerns worldwide.

The Future of the Suez Canal in a Changing World

Facing continuous challenges, the Suez Canal undergoes substantial transformations to maintain its relevance in global trade networks. As regional tensions and technological advancements reshape maritime commerce, Egypt’s vital waterway adapts through ambitious development initiatives.

Expansion projects and the New Suez Canal

Egypt’s vision for the canal extends beyond mere maintenance. The 2015 New Suez Canal expansion created a second channel section, enabling two-way traffic and reducing transit times from 18 to 11 hours. This groundbreaking project increased the canal’s capacity to handle 97 ships daily by 2023, up from 49 previously.

Currently, Egypt continues upgrading the waterway. In December 2024, authorities successfully tested a new 10km channel extension near the southern section, expanding the two-way portion to 82km of the total 193km length. This enhancement will accommodate an additional 6-8 ships daily, reinforcing the canal’s status as the shortest and safest global maritime route.

Technological upgrades and security measures

Alongside physical expansions, technological advancements strengthen the canal’s operations. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development launched the second phase of a digital transformation project for the Suez Canal Economic Zone, streamlining administrative procedures and establishing a fully automated one-stop shop for investors.

Essentially, maritime security improvements include the Automatic Identification System allowing real-time vessel tracking. Prime Minister Madbouly recently highlighted improved navigation security in the Red Sea, with attacks on vessels halting since December. Thereby, Egypt introduced incentives—including a 15% discount for large container vessels—to encourage shipping companies to resume canal transits.

Alternative trade routes and global resilience

Although the Suez Canal maintains its prominence, alternative corridors emerge. The Northern Sea Route along Russia’s Arctic coast could reduce Asia-Europe distances by 40%, potentially handling 8% of Asia-Europe trade by 2030.

Other developing alternatives include:

- The Middle Corridor (Trans-Caspian International Transport Route) connects China and Europe through Central Asia

- The India-Middle East-Europe Corridor, which potentially reduces transport times by 40%

- The North-South Transport Corridor linking India to Russia through Iran

Nonetheless, these alternatives face significant challenges—the Arctic route requires specialised vessels and lacks infrastructure, hence remaining primarily a backup option alongside the Cape of Good Hope route.

Final Words

The recent disruptions to Suez Canal operations reveal a fundamental truth about global trade: this narrow waterway remains both vitally important and remarkably vulnerable. Clearly, the canal’s strategic vulnerability transcends Egyptian borders, becoming an international concern with far-reaching implications. Throughout the connected waterways—including the Red Sea, Bab el-Mandeb, and Eastern Mediterranean—stability has proven essential for uninterrupted global commerce.

Securing this maritime lifeline requires multifaceted approaches. Egypt already maintains a robust military presence along the canal itself, yet the Red Sea attacks highlighted the necessity for broader cooperative security frameworks involving regional states and global naval powers. Given these points, several potential solutions emerge:

- Establishing multinational maritime patrols in high-risk periods (similar to past anti-piracy operations)

- Implementing convoy arrangements through dangerous zones

- Enhancing intelligence sharing and early-warning systems

- Addressing root conflicts through diplomatic channels (as evidenced when temporary Israel-Palestine ceasefires reduced shipping attacks)

- Coordinating policy through the UN International Maritime Organisation or concerned nations’ coalitions

Beyond security measures, the importance of the Suez Canal becomes evident in infrastructure resilience efforts. The 2015 expansion created a second channel, enabling two-way traffic and reducing transit times. Furthermore, investments in alternative route ports aim to handle diverted traffic during emergencies.

With this in mind, technological advancement plays an equally critical role in safeguarding what is arguably the world’s most significant trade chokepoint alongside the Strait of Hormuz and the Malacca Strait. Systems like the Automatic Identification System enable real-time vessel tracking for proactive threat response.

Ultimately, the Suez Canal significance extends beyond its original purpose of shortening east-west journeys. As a waterway handling 10% of global trade but 30% of daily global container traffic, its continued operation requires collaborative efforts among policymakers and industry leaders to ensure geopolitical conflicts do not again disrupt this essential trade artery.

2 Comments